Our journey to excellence in teaching begins with a commitment to professional learning.

-Regie Routman

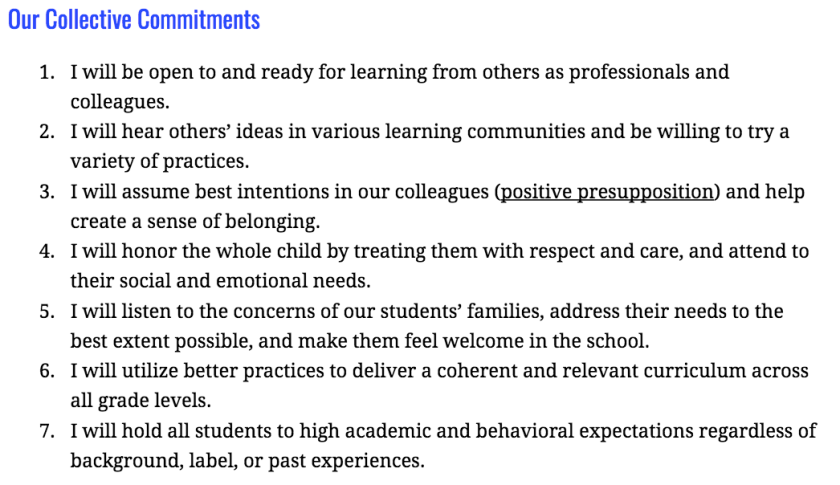

I am lucky enough to work in a school that believes in this so much that they allocate the money to have me on staff working with teachers in their classrooms every single day. Yes, that’s right. Every. Single. Day. Every Teacher. This beautiful hidden gem of a school only has one teacher per grade level K-4 so I get to be in their classrooms, learning side by side with the teacher and the students in every grade level every single day. My school lives what Regie calls professional learning over professional development and that is not easy to do. Imagine the teachers’ thoughts and feelings in this tiny school when they hired yet another support staff member (cue eye roll) instead of allocating the money towards their budgets or a teacher’s assistant. However, after one year, I think we have all realized now the power of having this kind of consistent learning that is specifically “connected to classroom practice and geared toward fostering collegial collaboration” (Routman, 2018).

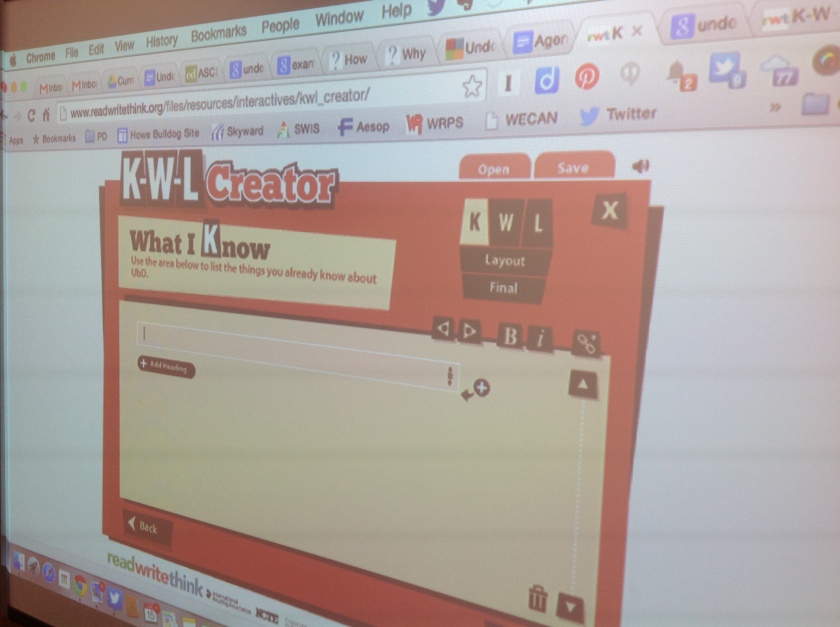

This year we all focused on writing with an emphasis on giving kids time to write every single day with purpose and an audience in mind. We worked towards creating a common language across the grade levels along with building writing skills and expectations from grade to grade. This is exactly the kind of collegial collaboration that is talked about in Literacy Essentials as being the kind of long-term growth and sustainability that schools strive for. Teachers are crazy busy and barely have time to go to the bathroom let alone talk to a colleague about best practices. Cue me. Showing up for them and with them every single day. I could tell the first-grade teacher what was happening in kindergarten and second grade. I could make her feel like she was a part of a bigger picture when teachers sometimes feel like they are on an island. I was able to not only ask, “How is it going?” but actually see how it was going. Turns out it was going well, really well.

As educators, we could reflect every single day on what we saw and what we could do next. I brought resources they didn’t have time to track down, I found research supporting their thoughts and beliefs and I cheered them on as they went out of their comfort zones to try new things. We only met as a group when the topic affected the whole group. I didn’t have to call meetings where people felt disrespected for using their precious time for things that don’t pertain to them. Individual issues, questions, and concerns were talked about and worked through each day during their classroom practice. I was able to glean and share our set of shared beliefs around writing and help the busy teachers keep a focus on those beliefs. We made a difference in our community of writers, in their enthusiasm for sharing their words with the world, their ability to grow as writers and it reflected (thank goodness) in their test scores. Teachers are now more confident when they talk to writers and have the common language to help support them.

I know our situation is an enigma, I know that you are probably not in this same situation and can think of a thousand reasons why this wouldn’t work for you, I know how lucky we are. I ask you though to instead focus on what can be done. If you are a coach and can’t physically be in each teacher’s classroom every day, what can you do to help if just in small ways? How can you facilitate communication between the teachers and help build collaboration? If you are a classroom teacher could you use your fellow colleagues as coaches when one person can’t do it all, or share in the responsibility for your learning and reflect on your practice even if someone isn’t there to push you? These are all thoughts Mrs. Routman shares with us in Literacy Essentials.

Professional learning over professional development works. When teachers are the “Lead Learners” in the classroom not only by words but by action, they inspire their student learners each and every day. I have lived it, seen the power of it, and can’t wait to see what next year brings.

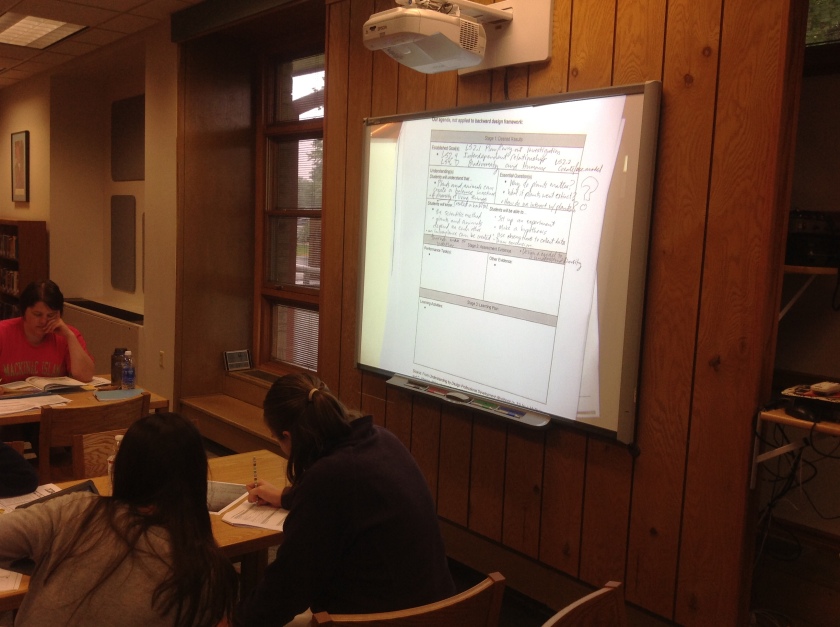

Over 20 teachers recently celebrated their learning as part of their work with an action research course. They presented their findings to over 50 colleagues, friends, and family members at a local convention center. I was really impressed with how teachers saw data as a critical part of their research. Organizing and analyzing student assessment results was viewed as a necessary part of their practice, instead of simply a district expectation.

Over 20 teachers recently celebrated their learning as part of their work with an action research course. They presented their findings to over 50 colleagues, friends, and family members at a local convention center. I was really impressed with how teachers saw data as a critical part of their research. Organizing and analyzing student assessment results was viewed as a necessary part of their practice, instead of simply a district expectation.