A book that piqued my interest in the principalship was Improving Schools from Within: Teachers, Parents, and Principals Can Make the Difference by Roland Barth (Jossey-Bass, 1990). During one of my first years as a teacher, I found it while browsing through our professional library. At the time I only knew I should probably go for my masters but I was unsure about any focus.

After reading Barth’s classic resource, I knew what I wanted to study. He shared his own personal journey as a principal, the ups and downs, before conveying his belief that empowered schools have all they need to continuously grow as a community of learners. Barth’s frank and authentic descriptions of the principalship are something I don’t often read about in today’s literature on school leadership.

Repositioning Educational Leadership: Practitioners Leading from an Inquiry Stance (Teachers College Press, 2018) carries Barth’s torch and follows a similar journey. The editors – James Lytle, Susan Lytle, Michael Johanek, and Kathy Rho – have collected a series of narratives from doctoral students at the University of Pennsylvania, Graduate School of Education. They are research summaries that describe the real problems of practice for these leadership students within their context at the time.

Among the eleven memorable experiences, I want to briefly highlight one narrative that hit home for me as a principal.

“Language and Third Spaces” by Ann Dealy

A principal in Ossining, New York explores the possibilities of implementing a more culturally-relevant curriculum into her increasingly diverse elementary school. What she discovers is that when leaders try to make instructional changes, they also have to consider the school culture and community in the process.

Professional development shifted from looking for answers from outside of the school to studying our students as learners and collaborating on changes in practice to better support teaching and learning (38).

Dealy also learned through her inquiry that, by upgrading a curriculum to be more culturally responsive, other groups may inadvertently experience somewhat similar feelings of being underrepresented.

It became clear that in the effort to open up curricula, we can also inadvertently close out those whose prior dominance we may have been countering (41).

This research helped reveal for Dealy and her partners that the process of organizational change is most effective as a team effort. Not taking into consideration others’ perspectives will likely lead to limited results.

The implementation of best-researched models of equitable practice is a start – but it is not enough. My leadership learnings include the necessity for collective inquiry to affect systemic change (45).

After reading Dealy’s narrative, I reflected on my own experiences when I have not included the broader school community in decision making on behalf of our students. Almost always when I have engaged with others regarding our schools’ needs, the direction we took was positive. The narratives shared in Repositioning Educational Leadership provided necessary perspectives for me as I considered my own context. It also brought me back to the original goal of getting into the principalship: to affect change from within and with many.

Note: A copy of Repositioning Educational Leadership was provided for me at no cost to read and respond to for this post.

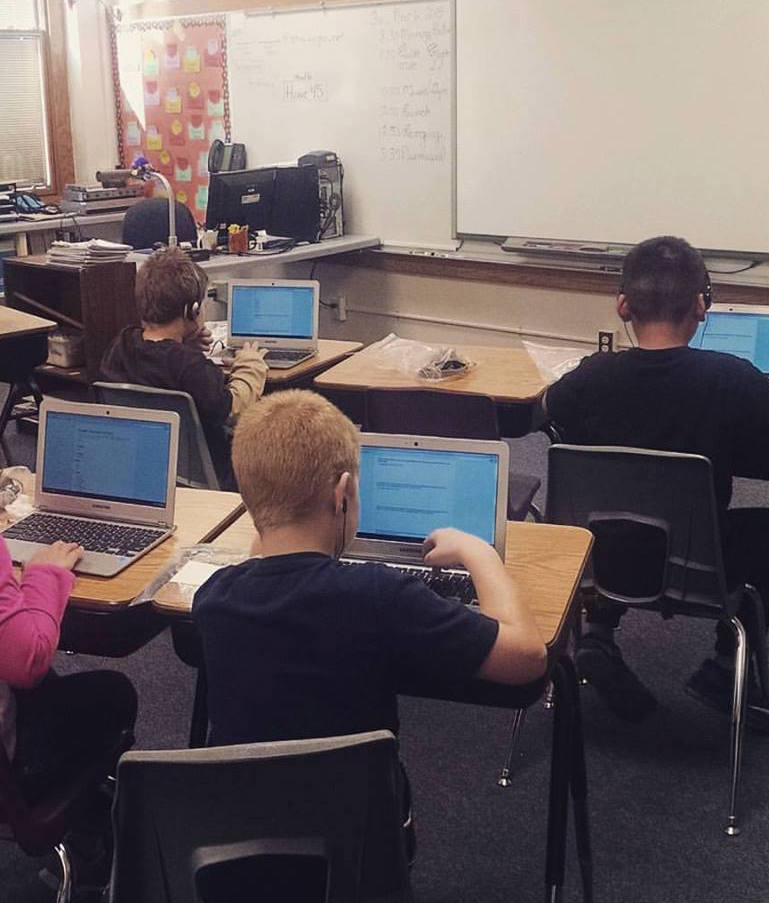

Over 20 teachers recently celebrated their learning as part of their work with an action research course. They presented their findings to over 50 colleagues, friends, and family members at a local convention center. I was really impressed with how teachers saw data as a critical part of their research. Organizing and analyzing student assessment results was viewed as a necessary part of their practice, instead of simply a district expectation.

Over 20 teachers recently celebrated their learning as part of their work with an action research course. They presented their findings to over 50 colleagues, friends, and family members at a local convention center. I was really impressed with how teachers saw data as a critical part of their research. Organizing and analyzing student assessment results was viewed as a necessary part of their practice, instead of simply a district expectation.