This post on Stenhouse’s blog is a follow up to my initial offering, Increasing Engagement. If you have a question, comment, or suggestion about this program, please share in the comments. I will respond.

Summer has arrived: Lockers have been cleared out, desks are empty, and report cards were sent home. While another school year comes to a close, ten reluctant readers are only continuing their learning.

Last fall, my school revamped our after school reading intervention program. Illustrated in our previous post, my staff and I designed a book club based on the tenets of Peter Johnston’s reflections from last summer, Reducing Instruction, Increasing Engagement. We transitioned from a computer-based reading program to an intervention that relied more on students’ interests than on their Lexiles.

Everything started strong. Kids came to book club eager to check out the new titles, selected just for them. The majority of the time was allocated to allowing students to read books, to talk about books, and to share what they read. The facilitator’s job was simply to spark their interest and gently guide.

For a while we had them – They were reading! However, interest gradually dissipated. Some students got off task. Others stopped showing up regularly. The perception was that this “book club” was just an extension of the school day. We had to rethink our approach.

We knew students were engaged by technology. But would purchasing tablets to promote reading provide too much of a distraction? We found our middle ground and purchased ten simple eReaders. These devices were unable to house games and other forms of digital media. Just books. While we waited for the eReaders to show up, students came down to my office in groups of twos and threes to request their favorite titles and authors. Once students had signed a contract and the books were loaded on the devices. we sent them on their way to read.

We quickly realized the benefits of offering eReaders to students:

- They were more willing to pick books they could decode and understand. On one occasion, a 4th grade boy rattled off some grade level titles, then looked around and whispered, “Could I also get some Flat Stanley chapter books?” I replied, “Sure” without missing a beat. Unless his books could be hidden within an eReader, it was unlikely he would have been caught by his peers reading Flat Stanley and related titles.

- The technology itself seemed to engage the students. I have never, as a teacher or as a principal, had students seek me out (repeatedly) to see if their new books were available and ready to read. Having kids peek their heads out of classrooms when they heard me walking the hall to ask when their books would be downloaded was a visible example of their engagement with reading.

- The buy in from parents was impressive. One parent made a special trip to school to pick up her son’s eReader. A father, whose son was home sick on the last day and came to pick up his report card, made a point to share with me that “he has been reading on that thing every day”.

When we looked at our year-end assessments, the results were a mixed bag. Analyzing computer-based screener scores, on average our ten students’ overall literacy skills stayed the same. However, looking at district-developed assessments, the majority of the students (70%) met their grade level benchmark, and the other three students were very close. In addition, their average fluency rate increased by 27% (92 Words Correct Per Minute (WCPM) in the fall; 117 WCPM in the spring).

Beyond this promising quantitative data, did our students develop an affection toward reading? Do they better value the impact a narrative can have on a person’s life? We attempted to measure engagement with a survey given to the students themselves. They were asked specific questions about their reading dispositions and habits; you can view the results here. Here are the most revealing conclusions:

- Students in book club read a lot more now than they did before joining book club.

- The eReaders encouraged the students to read more.

- Students understood what they read, whether in print or digital text format.

- They often reread their favorite books.

These statements read like they belong in a resource titled “The Seven Habits of Highly Engaged Readers”. We hope these practices continue, as we sent them home with both print and digital texts to peruse over the summer months.

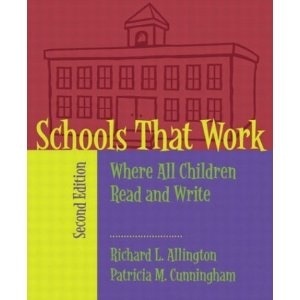

My teachers often state that teaching reading is not like baking a cake. Students aren’t “done” after a certain amount of time and attention. Maybe we should compare educators to gardeners instead of bakers; they plant the seeds for literacy engagement, to grow and eventually blossom. Readers are created over time and do not adhere to deadlines. Where learners are heading is as important as where they have been.