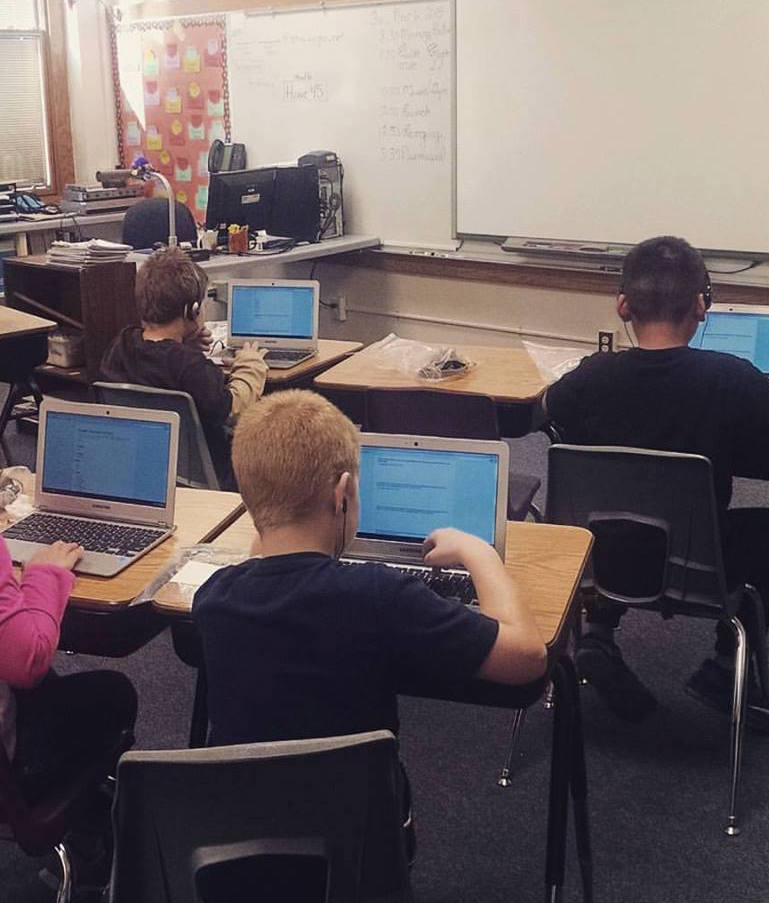

For the first time in a while, I had an open schedule at school. Daily classroom visits were completed. An instructional walk was conducted. Absences and requisitions were approved. When these opportunities occur, I try to read professionally at school.

When I first started reading professionally at school, I felt guilty. Would others think I was wasting time, believing I should be in classrooms and in the hallways whenever possible? I would close my door to avoid any judgment.

I’ve come to realize that reading professionally should be a top priority for literacy leaders. In order to be seen as credible in the eyes of our faculty, we have to be knowledgeable about teaching and learning. Reading professionally helps ensure that we are aware of new educational research that could positively impact students. Taking the time to learn from others through text models for everyone in the school how we should all spend our time.

Reading professionally doesn’t happen without forethought, communication, and intent. Here are some steps I have taken to make this part of my day a priority.

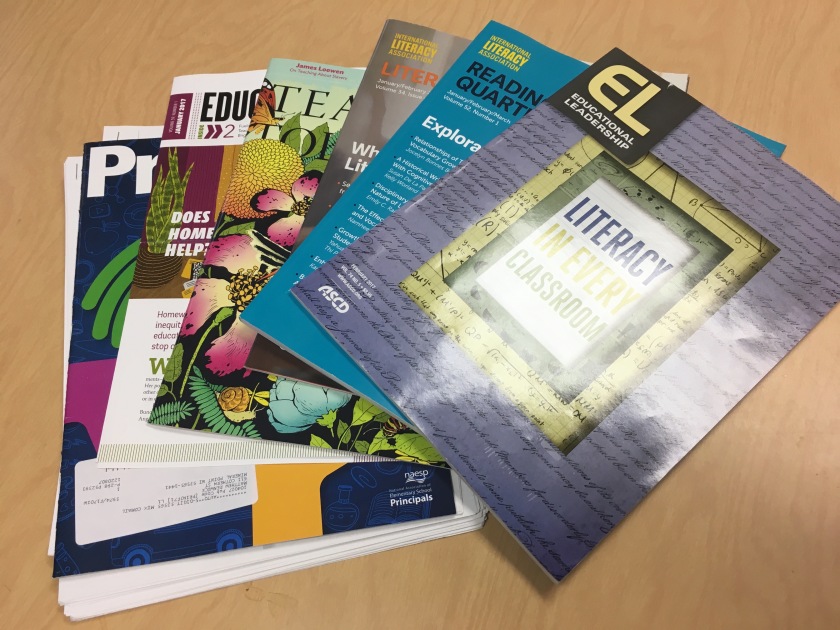

- Subscribe to professional journals and magazines.

I use school funds to purchase subscriptions to Educational Leadership and Educational Update (ASCD), The Reading Teacher and Reading Research Quarterly (International Literacy Association), Literacy Today, Language Arts and Voices from the Middle (National Council of Teachers of English), Teaching Tolerance (Southern Poverty Law Center), and Principal (National Association of Elementary School Principals).

- Schedule time for professional reading.

I’ve started putting this time on my calendar when I think of it. If it is written down, I am more likely to do it. That said, scheduling time for professional reading is less about making sure I am reading professionally, and more about communicating to my superintendent and my staff that this is a priority for me.

- Set a goal and share what was learned.

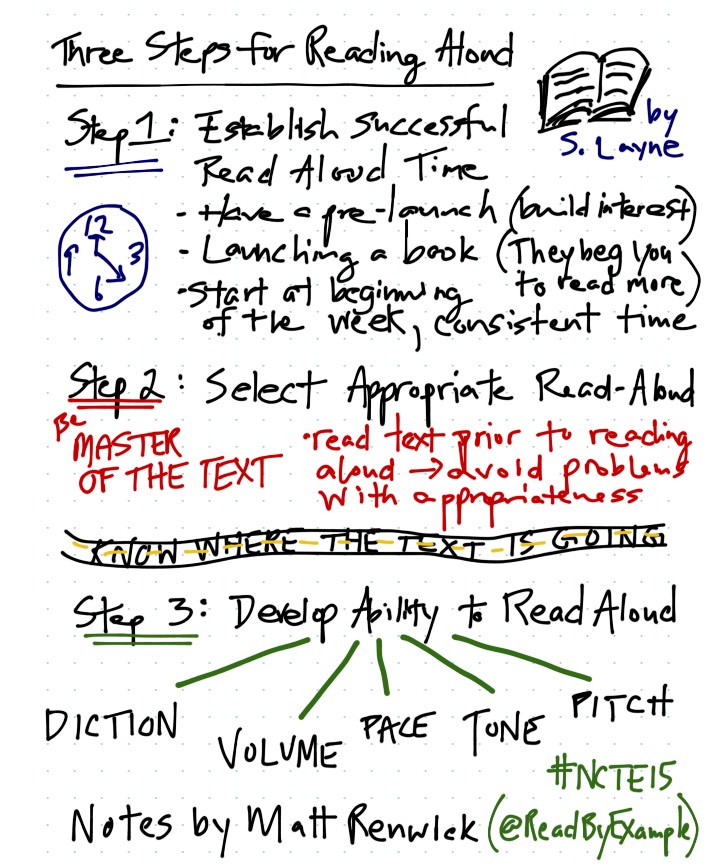

Regie Routman at the Wisconsin State Reading Association Convention suggested that school leaders read one article a week and share a brief summary with staff. This can be communicated through a weekly newsletter or even email, with the article attached. By the end of the month, four articles have been shared out. This information can be a way to start a staff meeting, by asking teachers to share their insights from one of the articles.

- Read professional books related to your goals.

I try to select texts that will have an immediate impact on my current professional goals and objectives. This is in contrast to picking up a book because it just came out and everyone is talking about it. I find that, in my limited time, I have to be selective about longer texts I choose to read. For example, I am halfway through The Together Leader by Maia Heyck-Merlin; my professional goal is to become more organized and efficient.

But how do I find the time?

I’ve been in situations where there is barely any time to go to the bathroom or have lunch, let alone scheduling the time to read professionally.

Not knowing anyone’s context, I have a few general suggestions. First, revisit your daily tasks. What should you be doing and what should you not? For the latter, find ways to reassign those tasks, find more efficient methods, or jettison altogether. Second, set no more than two priorities. I have two priorities this year: build trust and increase literacy knowledge. Anything else that comes my way I do my best to delegate, defer or dismiss. Finally, communicate with your supervisor about taking school time to professionally read. This gives you peace of mind when you open up that journal or book at school.

So what are you reading professionally? How do you find the time? Please share in the comments.